Titanium alloys may be strong, but they’re tough to machine! Thin sheet parts especially suffer from dimensional inaccuracies due to stress-induced deformation during cutting—a headache for many!

Don’t panic—a comprehensive solution can fix it: Adjust wire cutting and CNC milling paths, optimize machining plans, then enhance part rigidity with positioning fixtures and enclosed cutting methods.

This minimizes deformation at the source, ensuring consistent product quality!

Introduction

Titanium alloys boast high strength, corrosion resistance, heat resistance, and hardness, making them widely used in aerospace applications. Their drawbacks include poor thermal conductivity and challenging machinability.

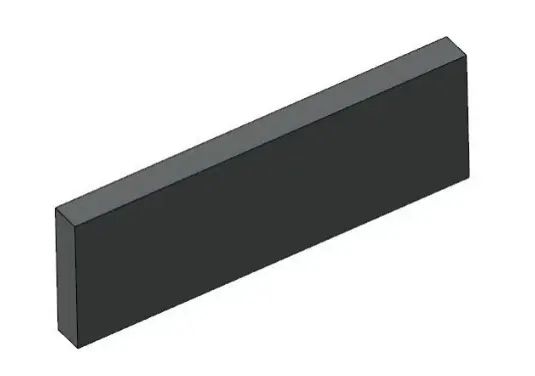

The titanium alloy spacer part measures 43mm in length, 25mm in width, and 3.5mm in thickness.

The thickness and two central cavities are CNC-milled, while the eight external ribs are wire-cut to ensure rib widths of (0.3±0.05)mm and cavity symmetry within 0.05mm—classifying it as a fine-rib component.

During initial production, 10 parts were machined according to the process document. Inspection revealed that 4 parts failed to meet design requirements due to deviations in rib width and symmetry.

Cause Analysis

The original process document specified a raw material thickness of 5mm. However, due to inventory limitations at the facility, only 18mm thick material was available.

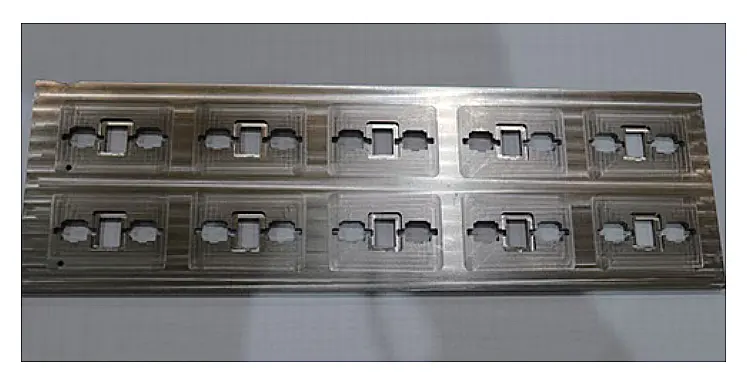

Consequently, the blank cutting dimensions were set to 250mm × 80mm with a thickness of 18mm, as shown in Figure 1.

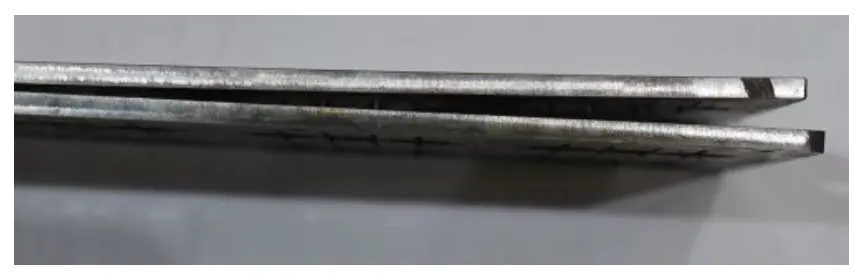

An additional wire-cutting process was incorporated to halve the material thickness (see Figure 2), resulting in 9mm-thick sections. These sections were then CNC-milled to a final thickness of 3.5mm.

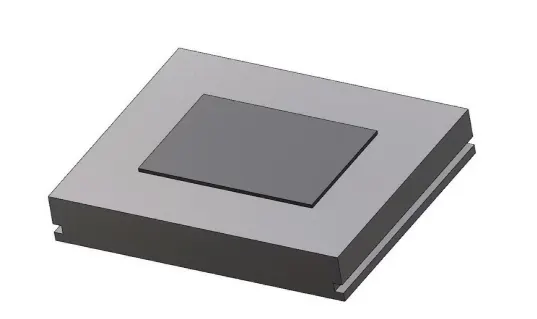

During CNC milling, operators use vacuum suction cups for clamping (see Figure 3). First, one surface is precision-milled to remove 3mm of stock.

After flipping and re-clamping the part, the second surface is milled to 3.5mm thickness. Finally, the internal cavity in the part’s center is machined.

Ten small parts are laid out per material sheet (see Figure 4). A 3mm center threading hole is drilled at one end of each row of parts. The parts are then transferred to the wire cutting process for shaping.

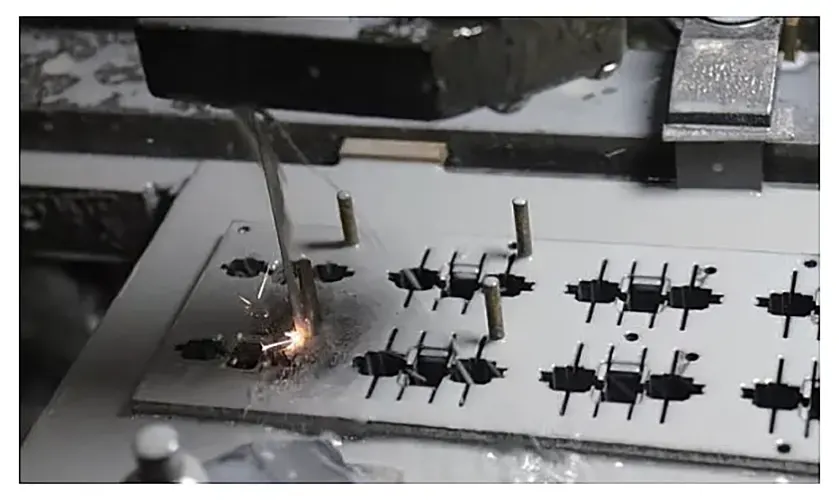

Before processing, the wire cutting operator inspected the material’s flatness and discovered stress-induced deformation (see Figure 5), with the maximum deformation amounting to 3.05mm.

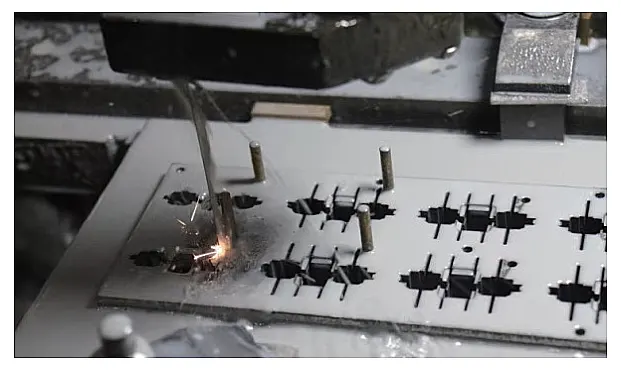

Using a clamping plate for cutting, with only one threading hole, the small parts became interconnected after cutting. The material was severed, causing deformation under stress during processing (see Figure 6).

This resulted in rib width dimensions exceeding tolerances, thereby affecting symmetry with the inner cavity.

Implementation of Effective Measures

Analysis revealed that the primary issue stemmed from material stress deformation. Titanium alloy generates cutting heat during machining and dissipates heat slowly.

The greater the material removal, the larger the resulting deformation. This could only be addressed by modifying the cutting method.

The original machining plan was optimized by implementing the following effective measures:

Replace high stress with low stress.

During CNC milling, larger cutting allowances generate greater stress, leading to increased material deformation.

The team modified the wire-cutting process for the raw material, changing the split from two pieces to three pieces (see Figure 7).

This resulted in each piece being approximately 6mm thick, significantly reducing the CNC milling allowance and thereby minimizing material deformation.

Modifying the CNC Milling Clamping Method.

The team replaced the vacuum suction cup clamping method with side-top clamping when machining thickness during CNC milling (see Figure 8).

The team repeatedly flipped the part to precision-mill both sides and limited each cutting pass to ≤0.2 mm. This ensured thickness compliance with drawing specifications while minimizing material deformation during processing.

Calculations indicate that post-CNC milling, controlling total material deformation within 0.5mm satisfies the flatness requirements for individual small parts.

Operators performed machining according to the optimized method, conducting in-process inspection to ensure flatness ≤0.2mm.

Fabricate specialized fixtures to increase wire-through hole count

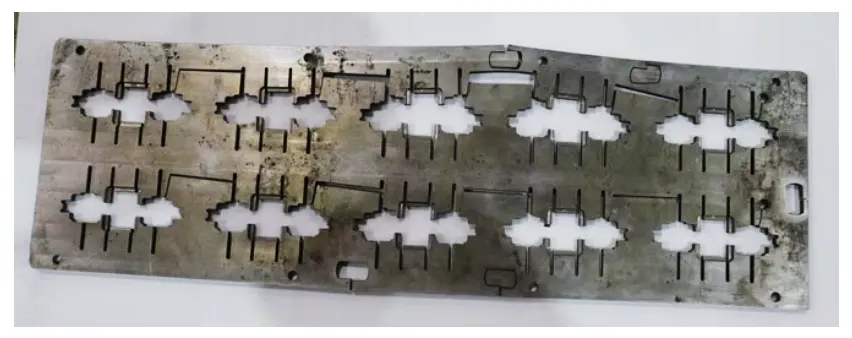

The team increased the number of wire-passing holes to 10 during wire cutting to prevent material deformation.

This ensures each spacer part has an independent wire-passing hole, formed in a single CNC milling operation to guarantee consistency.

Fabricate wire-cutting fixtures to position workpieces onto fixture plates using locating pins (see Figure 9). The process machines each spacer independently without interconnecting cuts, which enhances material rigidity and minimizes part deformation.

Effect Verification

The team trial-machined twenty parts according to the improved plan. Professional inspection equipment confirmed that all rib width dimensions and symmetry met drawing requirements.

The team processed all 120 parts in this batch to specification and achieved a 100% pass rate. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the improvement plan.

Conclusion

This paper presents a machining process and deformation control method for thin-sheet titanium alloy parts.

The team ensured the rib width dimensions and symmetry requirements by optimizing the machining plan and clamping method, modifying the wire-cutting path and CNC milling strategy, and using positioning fixtures with enclosed cutting to reduce cutting-stress deformation.

This approach provides valuable experience for machining similar parts.

FAQ

Why are titanium alloy thin-sheet parts difficult to machine?

Titanium alloys have high strength, poor thermal conductivity, and high hardness. These characteristics cause cutting heat to accumulate and result in stress-induced deformation—especially in thin-sheet parts—leading to dimensional inaccuracies such as uneven rib width or poor symmetry.

What caused the dimensional deviation in the initial batch of titanium alloy spacer parts?

The main cause was stress deformation from using oversized raw material. Starting with an 18 mm-thick blank (instead of the specified 5 mm) meant excessive material removal during CNC milling, generating significant internal stress. Combined with an insufficient number of wire-cut threading holes, the blank warped during both milling and wire cutting.

How was the machining plan optimized to reduce deformation?

The team adjusted the process by:

Splitting the thick raw material into three thinner sections to reduce CNC milling allowance.

Reducing cutting passes to ≤0.2 mm per side.

Switching from vacuum suction to side-top clamping to increase rigidity.

These steps minimized stress accumulation and improved machining stability.

How does modifying the clamping method improve accuracy?

The original vacuum suction method lacked sufficient rigidity for thin titanium parts. Replacing it with side-top mechanical clamping, combined with repeated flipping and precision milling, controlled part deformation within 0.5 mm and ensured final flatness within 0.2 mm—meeting design requirements.

Why was it necessary to add more wire-through holes during wire cutting?

Increasing the number of wire-through holes from one to ten prevented interconnected cutting paths. Each part could then be cut independently, maintaining material rigidity and reducing deformation during wire cutting. This greatly improved rib width accuracy and cavity symmetry.

What were the results of the improved machining method?

All 20 trial parts produced under the optimized process passed inspection. The remaining 120 parts were processed with a 100% pass rate, proving that the enhanced machining strategy effectively controlled deformation and ensured consistent product quality.