To the average person, burrs may seem like a minor issue, but they can actually have significant consequences. For instance, in precision aerospace components, burrs critically impact the safety and reliability of aviation products.

Their detection, assembly, and operational lifespan are all crucial factors requiring careful consideration—especially burrs on threads.

Characteristics and Risks of Thread Burrs

Thread burrs primarily occur at the crest and termination points of threads. Within system components, if thread burrs detach during tightening, they may be carried by fluid flow, potentially causing system blockages or electrical short circuits.

Burrs located near the seal groove at thread termination points can damage seals, shorten their service life, and lead to failures. Typically, thread manufacturing employs cutting methods such as turning, milling, grinding, tapping, and thread forming.

Limitations of Conventional Deburring Methods

For deburring, the primary methods can be broadly categorized into four types: manual removal, abrasive removal, specialized processing, and machining removal.

Among these four methods, manual deburring is the most prevalent and least costly.

However, manual deburring typically involves using burr scrapers or files for grinding. During this process, it is highly prone to damaging other precision-machined surfaces, affecting product quality.

Furthermore, the quality of deburred surfaces is often suboptimal, the labor intensity is high, and it demands a high level of skill from the operator.

Considering that thread turning is a highly prevalent machining method in the aerospace sector, this paper focuses on CNC thread turning as its research subject.

It explores how to rapidly and effectively remove burrs formed during thread turning using CNC lathe machining methods.

Mechanism of Burr Formation and Determination Standards

Analysis of Burr Formation Mechanism

Under cutting forces, the material on the machined surface undergoes plastic deformation. When the chip separates from the machined surface, residual material adheres to the part surface, forming burrs.

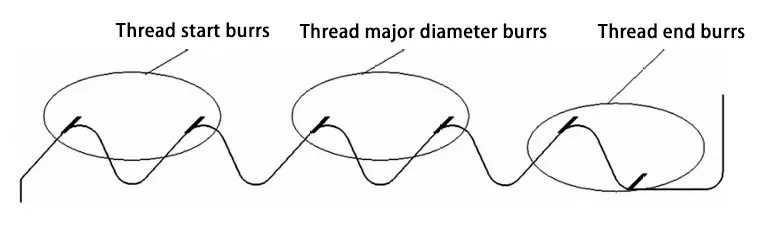

Taking external threads as an example, this paper observes the microstructure of externally threaded parts during turning, as shown in Figure 1.

Observation reveals that thread burrs primarily concentrate at the thread’s feed position, crest, and trailing edge.

At the feed position, compression between the tool and workpiece material causes localized plastic deformation to fold outward, forming burrs at this location.

At the thread crest, burrs tilt toward the feed direction. This is primarily due to the combined effects of radial and axial tool pressure.

Burrs at this location are prone to detachment during tightening, posing risks to system operational safety.

At the thread termination, burrs form at the junction between machined and unmachined surfaces.

These burrs are particularly sharp, with their inclination angle primarily determined by the retraction angle.

If located near the seal groove, such burrs can severely damage the seal.

Standards for Defining Burrs

Prior to part machining, process engineers must establish manufacturing plans and prepare technical documentation.

Typically, process drawings only specify part dimensions, surface roughness values, and positional tolerances, without quantitative definitions for burrs or other excess material.

This ambiguity prevents consistent worker judgment on burr removal, potentially resulting in parts failing to meet usage requirements.

GB/T19096—2003 “Technical Drawing: Terminology and Notation for Undefined Shape Edges” defines burrs as:

“Rough residual material outside the ideal geometric shape of an external edge, resulting from machining or forming processes.” In machining, common burr detection methods are listed in Table 1.

For detecting burrs on threads as discussed in this paper, visual inspection generally suffices to observe burr conditions across thread sections.

When quantitative analysis of burr height is required, quantitative methods such as projection measurement may be employed—the approach selected in this study.

Principles and Methods of Deburring

Deburring primarily involves removing burrs and flash from the start and end points, crest, root, and profile of threads.

Though thread burrs and flash are minuscule in size, they significantly impact thread connection performance—particularly in critical sealing applications where detached burrs compromise product longevity.

As product quality requirements continue to rise, particularly for aerospace and weaponry equipment, control over thread burrs has gained increasing attention.

Depending on automation levels, deburring methods are primarily categorized into manual removal and machine removal.

Manual deburring is typically employed when equipment automation is limited and part batch sizes are small.

The primary methods involve filing followed by sandpaper polishing. For harder-to-machine materials with high hardness, pneumatic grinding wheels or polishing wheels are often used to ensure effective burr removal.

Manual grinding methods suffer from low production efficiency, inconsistent product quality, and high labor intensity, making them unsuitable for large-scale production and delivery.

With the continuous advancement of machining equipment automation, automated programming enables rapid removal of surface burrs from parts.

For milled parts, chamfering tools can efficiently remove edges. For turned parts, burrs on edges can similarly be eliminated by rounding sharp edges.

Additionally, for threads, effective burr removal requires CNC programming tailored to the part’s dimensions, material, and precision requirements.

CNC Turning Process Design

Process Design

To investigate thread turning solutions, the external threaded straight pipe shown in Figure 2 serves as the study subject.

This fitting represents a typical flanged straight pipe primarily used in hydraulic system components.

Materials include aluminum alloy, stainless steel, and titanium alloy, typically processed on CNC lathes.

CNC turning was selected for machining, employing the process plan detailed in Table 2.

To visually demonstrate the presence of thread burrs under the aforementioned machining plan, a 50x magnification was applied using an optical measuring instrument. The burr effect is shown in Figure 3.

Analysis of Machining Plan

Analysis of the above machining plan raises the following issues:

1) During external thread turning, burrs are present at all thread major diameters and at both ends.

When manual filing is performed by a fitter using a rasp, the burrs cannot be completely removed in a single pass.

Repeated scraping at the same location is required. Furthermore, burrs are present on every thread pitch, with this phenomenon being particularly pronounced for threads made from materials with high plasticity.

This increases the operator’s workload. Additionally, this method has low processing efficiency and is not conducive to mass production.

2) Standard thread surface roughness is approximately Ra 3.2 μm.

Manual filing demands high operator skill, requiring precise pressure control that risks damaging thread surfaces and compromising quality.

Prolonged deburring often leads to missed burrs, potentially jeopardizing system reliability during part operation.

3) The aforementioned processing scheme necessitates transferring parts between machinists and toolmakers.

Increased part handling cycles prolong auxiliary time and reduce production efficiency.

Furthermore, during part transfer, components are susceptible to impact damage, severely compromising surface and thread quality and lowering the pass rate.

Optimized Process Plan

Analysis of the machining plan for the aforementioned part reveals sharp burrs on the major diameter and at the start/end points of the thread.

Based on an analysis of potential optimization points, the thread machining process has been optimized by adopting a multi-pass cutting approach to remove surface burrs from the thread.

Process Flow Optimization

Observation of burr distribution patterns reveals burrs primarily at the major diameter and thread ends.

To address this, a cylindrical turning tool can be directly employed for turning operations to remove burrs at these locations—effectively re-cutting the thread base circle.

The optimized process flow is detailed in Table 3.

Verification of Machining Effect

Based on the above analysis, using a cylindrical turning tool to cut the major diameter and ends of the thread theoretically enables burr removal.

To verify the machining effectiveness of this process, the external thread shown in Figure 2 was machined using a Hardinge T51 CNC turning center. The CNC programming G-code is as follows:

N20 T0202 //R0.8 external turning tool, the program is for rough turning the external diameter and major diameter of the thread, leaving a 0.2 mm allowance on each side.

N30 T0303 //R0.2 external turning tool, the program is for finish turning the external diameter and major diameter of the thread.

N40 T0404 //60° external thread cutter, the program is for machining external threads

N50 T0303 //R0.2 external turning tool, the program content is to perform one thread cut to the beginning, end and major diameter (increase the spindle speed appropriately).

The machining results are shown in Figure 5.

♦ Comparison of Conventional and Optimized Thread Machining Results

Comparison reveals that threads machined using conventional methods exhibit microscopic burrs on the crest.

In contrast, threads processed with the deburring technique show significantly reduced or completely eliminated burrs on the crest, resulting in substantially improved surface quality.

When machining materials with high plasticity, it was observed that adding an extra pass at the thread start/end and major diameter still left residual burrs on the thread crest.

The burr morphology changed from protruding above the major diameter to lying flush against the thread flank, becoming smoother.

Analysis reveals that this occurs because, under high plasticity conditions, when machining the thread crest, residual burrs continue to deform under tool tip pressure and redistribute along both sides of the crest, as shown in Figure 6.

♦ Additional Thread Profile Pass for High-Ductility Materials

To further address thread burrs in highly ductile materials, an additional thread profile pass is required either on top of the optimized process or the conventional threading scheme.

To enable optimal cutting effect comparison, stainless steel 1Cr18Ni9Ti serves as the test material due to its high ductility and toughness. The test cutting G-code is:

Figure 7 shows the machining results.

Comparative analysis reveals that the optimized approach of adding a thread profile pass significantly improves burr removal.

It completely eliminates burrs present on the thread crest, start/end points, and flank surfaces.

Concurrently, the thread surface roughness decreases substantially. Therefore, this method is particularly suitable for structures requiring high thread precision.

Conclusion

This study investigates thread burr removal on components, focusing on external threads.

Process optimization and cutting performance verification were carried out for external thread machining and burr removal. Repeated cutting passes on thread ends and major diameters effectively eliminate thread burrs.

For materials with good plasticity, minor burr residues may remain after repeated passes on thread ends and major diameters.

Reapplying the thread cutting process with a single pass along the thread profile can effectively eliminate residual burrs.

Of course, incorporating thread burr removal processes extends processing time to some extent.

Therefore, the selection of thread burr removal techniques should be based on the precision requirements of the thread and the machining performance of the material, balancing both processing efficiency and accuracy.

FAQ

Impedit egestas aliquet?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Sapien class quo temporibus?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Elementum voluptate sodales?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.